In January 2016, Francisko Du Plessis was diagnosed with heart failure.

Du Plessis was living in South Africa at the time of his diagnosis and was in and out of hospital for a year as they tried to sort out his chronic medications.

Initially the GP misdiagnosed him three times in the space of three to four weeks as he was struggling with moisture in his lungs, thinking that it was only a flu.

Eventually they sent him for an X-ray where it was revealed that he had an enlarged heart shadow.

After blood tests, the cardiologist called him in and diagnosed him with heart failure.

He then made regular visits to the cardiologist, adjusting his chronic medication to get it to an optimum level.

He started to feel better after a while and eventually went back to work installing heat pumps and air conditioning and living an active lifestyle.

Du Plessis moved his family to New Zealand in March 2019 for a better future for his three children. He found himself a cardiologist here and saw them on a regular basis. He was still on chronic medications, but he was doing well.

After moving to New Zealand, he started mountain biking and fell in love with the sport. “I was doing regular 20-50km bike rides with my friends,” he said.

Suddenly, in June 2022, within a week everything started crashing.

Francisko Du Plessis in Auckland Hospital in June 2022. Photo / Supplied

“My heart function went down and that started affecting all the other organs as well, everything started to shut down.”

Du Plessis could still walk, but he was drained of energy and a week later he could barely get himself up while in Tauranga Hospital.

“The cardiologist came in, sat at the corner of the room and rubbed his head in his hands and said to me, ‘We don’t know what to do anymore, we can’t treat you here anymore.’”

The cardiologist said that he contacted Auckland Hospital, as they are the heart specialists in New Zealand, who told him they wanted him in Auckland as soon as possible and that a helicopter was on its way to take him as an ambulance would take too long and might not make it on time.

He caught the helicopter from Tauranga to Auckland Hospital where he was checked. “They said my heart function was down to under 10%.

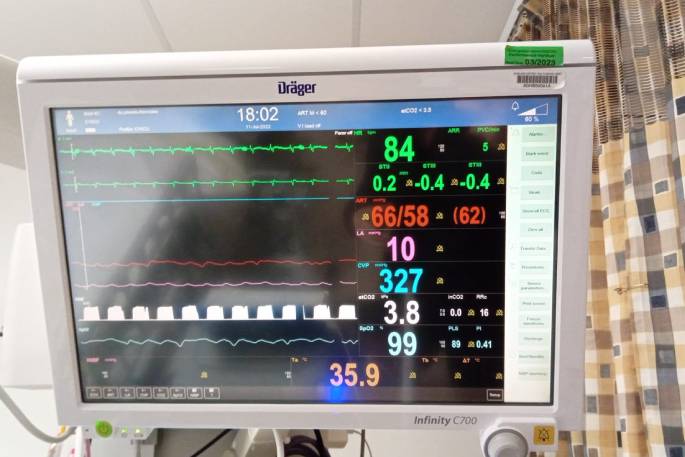

His blood pressure was at 86/54, it is supposed to be at 120/80.

“It was basically just vibrating; it wasn’t really pumping.”

Francisko Du Plessis's heart rate and blood pressure at one point while he was in hospital. Photo / supplied.

Francisko Du Plessis's heart rate and blood pressure at one point while he was in hospital. Photo / supplied.

After further checks and getting him stabilised the doctors told Du Plessis and his wife that he had less than six months to live.

A couple of hours passed, and they came back to say that they were wrong. He had a few weeks to live, “But, we’ve got a plan,” they said.

Two days later Du Plessis went in for his first operation on July 8, 2022. “They put in a little pump in my heart call an LVAD – Ventricle Assistance Device for the left side – because the left side did not work anymore and would not recover.

“New Zealand is one of the few countries in the world that uses the VADs only as a gateway to transplant, so your body can get stronger so you would be able to survive transplant. In many countries, for many people, the VAD is the final chapter. They say a VAD is only good for up to seven years.

“Then on the right chamber they had an external ECMO machine – extracorporeal membrane oxygenation – that’s also doing the work of the heart.

“Your blood is getting pumped, there’s pipes going into your groin, into your neck, through your heart and lungs and then your blood gets pumped through the machine and back through.”

They hoped that the right side would recover so that they could take the machine off and leave the LVAD, however, after a few days they said the right side was not going to recover and he was going to need an RVAD (Ventricle Assistance Device for the right side) too.

Francisko Du Plessis with his LVAD and RVAD. Photo / Bob Tulloch

When he went in for the operation to put in the RVAD they faced complications as blood clots that had become stuck in the pipe.

They had to take out the LVAD, clean it out, place it back in and continue.

This meant that the six-hour operation took more than 12 hours.

The day after his surgery he had to return to the theatre again due to internal bleeding.

This totalled three open-heart surgeries in the space of less than two weeks.

Du Plessis had two battery packs with controllers that regulated the two pumps. Each bag has two batteries and a controller with built-in back-up batteries. He had extra batteries as he had to recharge them and switch them over.

“If the battery goes flat, an alarm would go on and I’d have about 30 minutes to swap out the batteries,” he said. “You get about 20 hours out of the batteries.”

After the series of operations, Du Plessis slept in a medically induced coma for three and a half weeks in the cardio ICU.

Sometime during the process of putting in the RVAD, a small blood clot went through his system, causing him to have a mini-stroke.

This meant that while he was in recovery, he found that his right side didn’t work as well as it should, especially around the right shoulder and arm and his face on the right side was a little droopy.

“When I woke up, I had gone down from almost 100kg in weight to 63kg.

Francisko Du Plessis in Auckland Hospital in June 2022. Photo / Supplied

“That’s more than a third of my body weight gone. There was no muscle in my arms, I couldn’t lift my arms or legs up.

Francisko Du Plessis at Auckland Hospital. Photo / Supplied

He had a tracheostomy tube in his throat and wasn’t able to talk, even afterward, it took a while before he could speak properly.

Du Plessis spent two and a half months in ICU in Auckland Hospital and was getting physio to learn to walk and talk again.

After his time in the ICU, he went to a stepdown ward for three and a half weeks for further physio and recovery and then he spent three and a half weeks in a rehab centre called Hearty Towers for lung and heart transplant patients.

Francisko Du Plessis in Auckland Hospital in June 2022. Photo / Supplied

“I met a lot of wonderful people there. Everybody’s got their own story and it was really special to hear them all and learn and support each other.

“I was only the fourth person in New Zealand ever to have a BiVAD.”

Du Plessis shared stories of some of the people he met while he was in the rehab centre, people with stories similar to his. He spoke about how some of the people he met have since passed away due to complications and how some of them were holding on and hoping for a chance at transplant, at life. Because Hearty Towers is not only for post-transplant but also pre-transplant people getting tested to go on the active transplant waiting list.

He showed The Weekend Sun a photo of the transplant patients at the rehab centre telling their stories and how many of them had sadly passed since.

At the end of October in 2022, he finally got to go home with all of his cables and battery bags that his nurses since nicknamed his Louis Vuitton bags.

Francisko Du Plessis at Auckland Hospital with his "Louis Vuitton" bags. Photo / Supplied

During the entire time Du Plessis was in and out of hospital over the years his wife Adelle made sure to keep his spirits up. “She was there the whole time.

Francisko Du Plessis with his wife Adelle. Photo / Supplied

“Every week she would be there, even while I was asleep she would be sitting there next to my bed.”

Adelle had tried to explain to their children Mckenzie (now 12), Mckayla (now 10) and little Francisko (now 8) as best she could about the difficult subject.

Francisko Du Plessis with his kids little Francisko, Mckayla and Mckenzie. Photo / Supplied

“They came to visit me in hospital one time after I woke up, but I was still looking like a skeleton. My wife never brought them in again for quite a while.”

One of their children experienced an anxiety attack seeing their dad in his state. They were hyperventilating and they have been struggling mentally since the traumatising event.

Du Plessis said that it was as if they were angry at him for almost leaving them behind.

During the time that Du Plessis was in and out of hospital, Adelle had taken on full responsibility of keeping the family going.

“On Monday morning, she would take the kids to school and then she would shoot off to Auckland and then the kids would go to different friends for the week.

“We were really blessed to have good friends around us, all with kids, that opened their homes for our kids and also supported the and us hugely, even emotionally and financially, too.

“There were so many wonderful people from all over the world that pitched in, I heard of prayer groups in a few different countries which is really humbling.

“It was hard on the kids because they only got to see each other at school and only got to see their mum on weekends.

“Later on my wife organised a nanny, so after school they would go home and be together with the nanny looking after them for a few hours before taking them to the different houses.

“My wife would come to Auckland and be there till Friday morning and then she would drive back to spend time with the kids on weekends.”

Between all of this, Adelle was responsible for earning an income to keep the family going. Without residency, the family was unable to get government funding to help.

“My wife has a small business that she was trying to get off the ground, so in between being in Auckland, and running a small business and looking after the kids, she worked her backside off.”

When Du Plessis returned home from his almost four and a half month heart ordeal, his family was very happy to have him home.

“My kids just wanted me to go do stuff with them.”

Francisko Du Plessis with his kids Mckenzie, Mckayla and little Francisko. Photo / Supplied

He has been taking his kids out individually to spend some one-on-one time with them.

In November, Du Plessis’s parents came over to visit from Australia, “and they were so kind to bring my Covid,” he said jokingly.

“I was going to go on the transplant active waiting list at the beginning of December, but of course, I got Covid in November so they said ‘no’ and that I had to wait a seven-week step down period.

“Finally in January 2023, I went on the active list. I was on a waiting list for 19 days and I got the call. I was really lucky.”

Due to having one of the most common blood types, he had a much better chance of getting the call much earlier than some, but there is still a list they had to tick off for everything to line up.

Some people have to go through all kinds of tests just to get on the active list and some don’t get on it because they are not sick enough, all because there are not enough donors.

“One of my transplant buddies had to wait about 18 months for his transplant.”

On the day he received the call, he had woken up that Monday morning sitting up in bed getting dressed excited to go back to work after seven months because his company was finally able to have him at work safely.

“Then suddenly, my phone rings and it’s the transplant co-ordinator and she goes, ‘Cisko, we need you to go to Auckland very quickly we might have something for you.’”

Du Plessis packed his stuff into the car and headed to Auckland. “You think you are ready and prepared, but I was a mess that morning trying to organise everything, including the kids.”

He was nervous, excited and relieved to be getting rid of his “Louis Vuitton bags” that he had been carrying around with him for seven months.

He arrived in Auckland just after 12pm and that evening at just after 5pm he went into the theatre.

“It was a 14.5 hour operation, normal heart transplants take six to seven hours.

“They struggled to get the pumps out because my lung grew over one of the pumps.”

Eventually, the pumps were out and he was ready for the transplant.

“There’s a timeline they have,” Du Plessis said referring to the part where the surgeons perform the transplant.

“They need to get it in within 45 minutes. There were complications and stuff so they struggled with me so they went up to an hour and a half.

“They struggled to get the new heart going, there is always a risk of complications and then I was on blood thinners as well for my pumps to prevent blood clots and stuff getting stuck in them and so they went up to an hour and a half and I bled out on the table too, one of the surgeons on the team that did the transplant said to me.

“They had to replace about 80% of my blood.”

“On top of these struggles, one of the anaesthetists had a big fight on their hands trying to keep me asleep after the operation too,” he said jokingly.

“After the surgery, I was placed in a medically induced coma for six days to allow the heart to rest and recover. Normally it is about two to three days, but I had the ECMO machine on again to give the new heart a rest to recover from it all.”

When he went in for surgery he was at 88.9kg and after the six-day coma, he was down to 77.2kg.

On day seven he went into rehab and when he woke up he said he could feel the energy.

“It was crazy. I could feel the blood rush through my ears and my toes felt warm. They hadn’t felt warm in quite a long time.”

At night he wouldn’t sleep, instead he would lay there listening to the sound of his new heartbeat.

On the second day after waking up, they wanted Du Plessis to start walking.

“I’m used to struggling and running out of breath because of the pumps not getting the oxygen through the muscles.

“And then, after going about 30m, I realised, this is different. The oxygen is there, the energy is there, I looked at the physio and the nurse pushing the drips and said to them ‘Okay, keep up’.

“I started going faster, and they just had to run behind.”

Du Plessis said he was surprised with how quickly he recovered, “My body just went with it, and that feeling of life, it was just incredible.”

After heart transplant surgery, patients are given a 12-week caution period to prevent any damage to stitches in the sternum. Du Plessis had eight wires holding his chest together and didn’t want them to crack open.

“They asked me if my heart could go to the university for tests and if I am willing to donate my valves if they are still usable, I said yes to both. Afterwards, within three months they have contacted me on different occasions to let me know when they have used a valve, they saved two toddlers and a baby with three of my valves.

“When I got to rehab, the transplant co-ordinator said to me, ‘You’re going to be here for about a month and a half'.

“So I looked at him and said, I’m going to be home in three weeks and he laughed at me and said ‘I know you are very driven Cisko, you’ll probably make it work'. I was home in three and a half weeks.”

Du Plessis was unable to return to work for another three months after leaving rehab and started back in April 2023.

“It didn’t take long until I was back to full power at work.”

“After the transplant and I went back to work, I found myself a new aim.” Du Plessis wanted to compete in the Whaka100 mountain bike race, the largest mountain bike event in the Southern Hemisphere. I decided I wanted to do the 25km race.”

Francisko Du Plessis after finishing the Whaka25. Photo / Supplied

Du Plessis completed the race and even came 360th place out of around 600 riders.

Since he has continued to participate in the event, competing again in the 25km race in the e-bike division.

Francisko Du Plessis's medals from the Whaka 25 mountain biking event. Photo / Bob Tulloch

He was in for seventh place before falling over the handle bars 2km from the end, breaking his wrist. He continued the race with one hand and finished in 17th place.

Francisko Du Plessis after finishing the Whaka25. Photo / Supplied

Du Plessis continues to travel up to Auckland for check-ups with a cardiologist and says it only took a month after his transplant surgery to start to feel better than he ever had.

His energy levels were much higher than before because he had been living with a heart functioning at about 25%. Normally people have between 50%-70%.

The whole experienced has completely changed the way he sees life, he said he’s less quick to judge and sometimes it’s hard to tell when someone is going through the worst part of their life and he’s more understanding now. “Something small for you might be the biggest thing someone else is going through.”

Going through all of this has brought about many psychological challenges. “The first couple of weeks in hospital [after his transplant surgery] I cried a lot thinking about it, lying there listening to your heart and you think about that family that had to make that choice of organ donation while still in shock of losing a loved one.

“Around the one-year mark, at the beginning of this year, I suddenly had a mental breakdown again, we had lost four transplant bodies in the space of two to three months.”

Du Plessis started seeing a psychologist to work through it.

When asked what he would say to someone considering become an organ donor he said “You will be a hero, you will change not only the recipient’s life, but also their kids’, their family’s and everyone around them.

Francisko Du Plessis with his kids Mckayla, little Francisko and Mckenzie and his wife Adelle. Photo / Supplied

“Just having that time back with my kids, it’s the greatest gift ever.

“There’s a lot of people on the list, a lot of people needing organs and there isn’t very many donors, even though there could be.

To those needing an organ he said, “Keep on fighting. You have to keep positive, you have to keep fighting because as soon as you have your body in a state of positivity, the body just kicks into overdrive and tries to fix it. Don’t lose hope.”

Du Plessis is encouraging people to have the conversation with their families. “Why not save a life for free, you don’t need it anymore and your soul has gone to a better place.

“Have that talk with your family and those closest to you, let them know your wishes to donate because you never know what happens tomorrow and when your soul has moved on and only the body is left, they will have the final say what happens to it.”

Du Plessis is massively grateful for his donor and their family. They made the tough decision that ended up saving his life and letting him spend more time with his kids. To him and his family, they are forever heroes.

Organ Donation New Zealand’s Thank You Day is coming up on Saturday, November 30 for organ donation recipients across the country to come together and thank their donors.

This is a day of appreciation to all those who make organ donation possible.

Organ Donation New Zealand is responsible for deceased organ and tissue donation, a complex and sensitive process that is only possible in specific circumstances and with the support of a donor’s family.

Last year, with the support of their whānau, 64 deceased people donated organs following their death, leading to more than 200 people receiving lifesaving kidney, liver, lung, heart or pancreas transplants.

Thank You Day is a special opportunity to express gratitude to every donor and their whānau, as well as the many others involved in making these donations possible, including clinicians and hospital staff, laboratory technicians and scientists, the coronial service, those involved in the safe transportation of the organs, and more.

It’s also a powerful reminder for all New Zealanders to have a conversation with their loved ones about organ donation, to make sure their wishes are known. This simple act of communication can have a profound impact, as one organ donor has the potential to transform the lives of up to 10 others.